As the novel coronavirus became front and centre in people’s lives, it is no surprise that internet communities were impacted by it as well. Public groups, social media pages, and community spaces became flooded with discussions on the COVID-19 pandemic. Posts about cures, data, new information, and the proper way to wear a mask and wash your hands are a few of the themes that users saw across their screen throughout these past few months.

By Scott DeJong

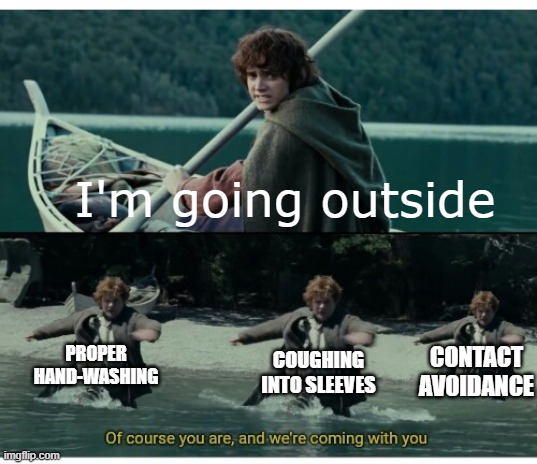

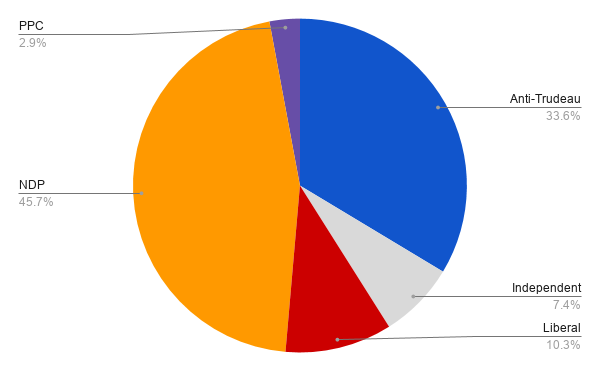

In our work tracking Canadian political meme pages on Facebook and Instagram, we noticed that these groups quickly integrated the pandemic into their discussions. Political meme pages have held true to their initial objective. Anti-Trudeau and anti-Liberal pages are still using memes to attack the Prime Minister’s character, question the party’s policies, and promote conservative ideology (see below). Meanwhile, pro-Liberal and pro-NDP groups still call for social reform and attack right-wing ideology while displaying varying levels of support for government responses to the pandemic. The pandemic has thus become the backdrop for the messages that meme formats and humour communicate to their audiences.

Attacking the Liberals and Trudeau

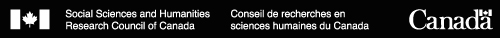

Holding true to their political partisanship, conservative-leaning groups contextualized their memes around COVID to continue making attacks against liberal policy. Figure 1 highlights the common conservative framing of welfare recipients as undeserving or lazy (Redden, 2011), and the Liberal governments’ Canada Emergency Response Benefit is mocked as overly generous. Posts like this were found across meme pages, where conservative groups used public concern and government responses to the pandemic to attack liberal or NDP ideology. Posts from anti-Trudeau and pro-Conservative groups also exploited the early stress on supply chains and public fear about shortages as attacks against socialist ideology.

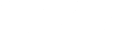

Ideology isn’t the only thing being memed. COVID-19 can just as easily be leveraged to attack a leader. In our sample, this leader is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Mainly from anti-Trudeau meme groups, posts attack Trudeau’s character and past blunders but contextualize them around COVID-19. As an example, Figure 2 presents four images of the Prime Minister in relation to recent purchasing limits at stores. In one image, Trudeau wears a ceremonial headdress bestowed to him by the Tsuut’ina First Nation (CBC News, 2016). Directly below it Trudeau appears in brownface, an infamous scandal from the last election. Even though these images depict markedly different moments of cultural (in)sensitivity, the memes bring them together to suggest that Trudeau will wear anything to avoid rationing at Walmart — or at least that’s the joke. Schill (2012) describes this relationship between image and political messaging as the enthymematic function of visual arguments, where disconnected political ideas are brought together through visual rhetoric. In short, memes become the scaffolding to recirculate attacks on Trudeau’s character and sincerity.

Social reform and attacking the Right

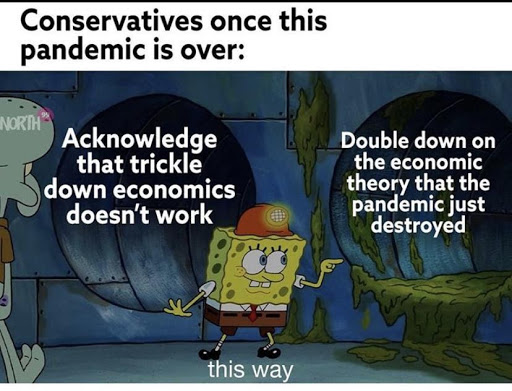

Unlike the memes typically found on the conservative pages, pro-Liberal and NDP memes typically used common meme formats rather than create their own meme. These templates reference popular culture such as Spongebob (see Figure 3). However, in some instances the format itself, rather than the message of the meme, became the subject of controversy. For example, during the Black Lives Matter protests, a pro-NDP page posted a meme using a common format that features musician Drake (Figure 4). Commenters immediately called out the post, critiquing the use of Drake’s image due to sexual harassment accusations against the artist. While the commenters still appreciated the overall message of the meme, they were clear in standing against the use of the chosen meme format to communicate it. In this case, the initial poster eventually edited their post to apologize for using the format.

In left-leaning coronavirus memes, the targets were not just political leaders. Figure 5 shows a common meme template used by a pro-liberal meme page to humorously highlight the perceived ideological hypocrisy of anti-vaccine proponents, referencing the consistently disproved claim that vaccines cause autism.

Memes from pro-Liberal and pro-NDP groups maintain a rhetoric that either attacks conservative ideology (like the reference to trickle down economics in Figure 3), or attempts to call for more comprehensive social reform. The latter aspect has recently become more prominent with discussion and support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

While some pro-NDP groups offered minor critiques of Justin Trudeau, their pages are less likely to attack individual politicians but instead critique the conservative or liberal ideologies as a whole. In doing so, the pages also push their own political convictions, such as being pro-vaccine.

Conclusion

Since the meme pages in our sample existed prior to the pandemic, they had already constructed an audience around a constitutive type of humour. As Milner and Philips (2017) discuss, memes invoke a constitutive humour with their audience, establishing an us-versus-them mentality. With the pandemic becoming a societal concern after these meme pages had already established their audience, it makes sense that these groups continued the work of maintaining partisan bonds. While not necessarily tied to specific political parties, the pages still maintain a distinct political agenda connected to certain partisan ideologies. Our findings confirm existing literature that highlights how political humour can be a “vehicle for serious political engagement” (Davis et al., 2018, p. 3912). As early memes show, political tropes have not disappeared with the arrival of COVID-19. Rather, political meme groups have adapted and created content that frames the current situation through previously articulated positions and critiques.

References

Davis, J. L., Love, T. P., & Killen, G. (2018). Seriously funny: The political work of humor on social media. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3898–3916. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818762602

Milner, R. M., & Phillips, W. (2017). The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Polity.

Redden, J. (2011). Poverty in the News. Information, Communication & Society, 14(6), 820–849. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.586432

Schill, D. (2012). The Visual Image and the Political Image: A Review of Visual Communication Research in the Field of Political Communication. Review of Communication, 12(2), 118–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2011.653504