By Meaghan Wester and Sophie Toupin

The Making of a Report on ‘Media Governance After AI’

Workshop Memo December 14, 2021

Participants: Janna Frenzel, Luciano Frizzera, Rob Hunt, Saskia Kowalchuk, Fenwick McKelvey, Jonathan Roberge, Sophie Toupin, Meaghan Wester

Collective Mapping, Translation, Partial Knowledges, and Situational Analysis

Where is AI being used in Canada’s media system? More so, what is Canada’s media system? Before Omicron closed campuses again, our team gathered for a workshop based on situational analysis to collaborate and theorize AI’s regulatory uptake in Canada. Here we want to share our approach oriented around situational analysis.

The Stack as Situation

The workshop marks the beginning of our SSHRC funded-project Media Governance after AI investigation into AI governance and governmentality in what we have come to colloquially call the Canadian AI ‘stack’. We use the term stack since the Internet is often imagined as a mega-structure that is composed of layers (such as applications, networks, etc.). The stack usually has 7 technical layers with politics and governance often described as the higher layers. It’s a metaphor, a diagram to begin our thinking about what is Canada’s media system.

We selected four topics as probes to shed light on this AI stack: 1) the use of AI in data centres, 2) the Canadian AI suppliers list and AI powered botnets, 3) the deployment of artificial intelligence in advertising, and 4) the deployment of artificial intelligence in TikTok’s content recommendation systems.

From these probes, our workshop sought to find their relations and commonalities. We were inspired by situational analysis as an innovative extension of grounded theory. In the approach, the situation becomes the main unit of analysis. It consists in mapping the situations that constitute each topic to layout the major human, non-human, discursive, affective, geopolitical and other elements in the four research situations under study. In our workshop, the stack became our situation.

Situational Analysis in Practice

On December 14, 2021, we collected ourselves to assemble a Canadian AI stack. Four research leads had investigated our four topics over the summer and the workshop began with them reporting back findings.

Situational analysis guided our interactions and discussion. As a methodology, situational analysis seeks to analyze a particular situation of interest through the specification, representation, and subsequent examination of the most salient elements in that situation and their relations. It was developed by the American sociologist Adele E. Clarke, and it emphasizes the following elements all of which have served as an orientation for the workshop and the subsequent report writing:

- Mapping as an analytic strategy

- Emphasis on reflexivity of researchers

- Emphasis on difference in data

- Emphasis on silences and absent positions

- Emphasis on nonhuman elements

- Emphasis on power

The workshop was composed of 8 participants including 4 area experts (i.e., students whose findings following their research were discussed). Accordingly, we proceeded to do four rounds producing each round one map on the topic at hand. Each round took place in the same fashion.

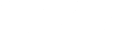

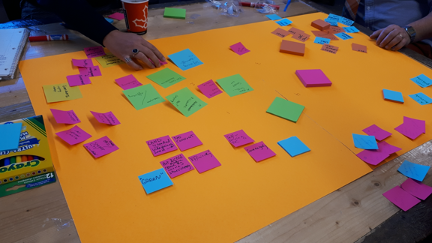

The area experts presented their summer findings for 15 minutes. While talking the other participants wrote on post-it notes salient points, keywords, related questions in order to visually and spatially represent the provided information. When the area expert was done presenting a summary of their findings, other participants asked questions, raised interesting observations and connections. During this discussion phase, post-it notes were moved around on the cardboard map while some were added to reflect the discussion that was taking place. Importantly, this process of discussion and representation engaged principles of partial knowledges, translation as well as reflexivity as we collectively co-created the messy map.

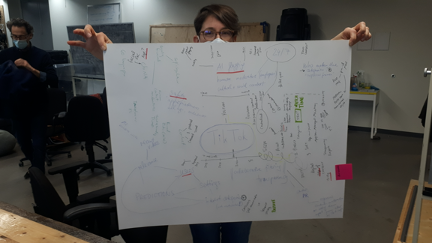

Once we had produced four area experts’ maps, we moved to the second phase of the workshop which was meant to orient how this information may be represented as a diagram or a ‘stack’. We collectively crafted categories to rehash and re-organized the post-its. The aim with the categories was to create cross-references; we came up with 4 pairs of topics (controversy/policies, infrastructure/machine agencies, time/space, suppliers/buyers) that we felt would enable us to unfold major themes and help structure our report. We freely posted the post-its inside the categories or on their borders. Once we had moved all post-its from the maps to the categories, we discussed the clusters that emerged and our choice of category headings.

Everyone attending left with an assigned category and the adjacent post-its. As a homework, participants were tasked to reflect on the category they had chosen and its relation to the post-its with the aim of synthesizing discussions and creating transversal themes across the four topics under study.

The purpose of the workshop was to move from individually imagining a situation to a collective understanding of that same situation. The richness of the collective process brought to the table each of the participants expertise and standpoints. Throughout the process, we paid close attention to what was missing on our post-its as we came up with the categories, as well as what did the categories failed to capture in turn producing leftovers.

Outputs

During this workshop, we co-produced:

- 4 maps of the four expertise areas

- 8 sister categories (4 pairs)

- 8 memos following the workshop that will serve as a basis for the report’s structure.

We are planning to use this workshop as the basis for a report to be developed in 2022. Less tangible, the workshop not only assembled an AI stack, but re-oriented our research team around a shared theorization.

Limits

As a first try, we learned a lot of how to improve future workshops. After discussing with the participants, we identified two main points to improve future workshops.

- Some participants voiced the lack of clarity on how to put together common expertise. Before we began the workshop, participants were unsure how the exercise would unfold in practice. This could be remedied by showing slides at the beginning of the workshop where we briefly explain past workshop iteration, and model what is expected from the participants.

- Another limit we encountered was the production of four different maps. One suggestion to avoid the multiplicity of maps, is to work on the same piece of paper for all area experts presentations. There are two main reasons why this could improve the overall experience and output of the workshop. First, by working off the same map, the participants could more naturally link together ideas by placing post-its in proximity with one another and placing arrows to show relationality. As such, we would produce a more relational pool of data which is what we were aiming for in the synthesis part of the exercise. The second reason why working on the same map would be beneficial is because the group could start producing the transversal theme together instead of leaving it on the participants during their memo drafting. This would again force a very productive process of translation and reflexivity.

Next Steps

Following this workshop, each participant is expected to send their memo on their assigned categories to a member of the team to start organizing the structure of the report.

We are hoping to test and improve this methodology with other research processes.