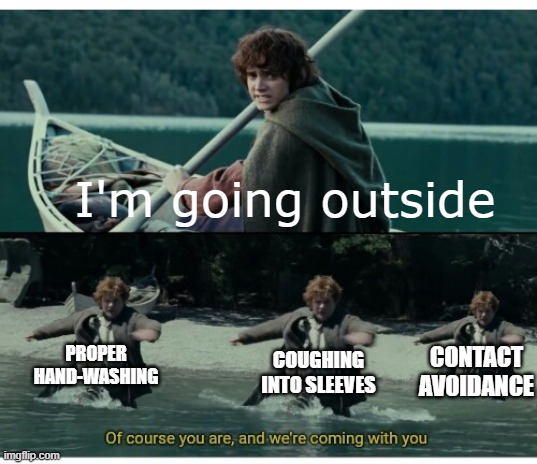

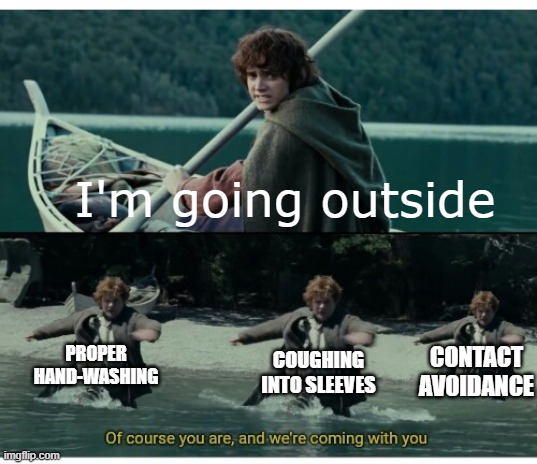

This post discusses how we research memes. Studying memes has been an iterative process for our team. Since we started in September 2019, we have revisited our methodology numerous times to effectively develop a mixed methods model. Our work was focused on political memes, which meant we prioritized the collection and analysis of memes from partisan communities that supported a particular political group or ideology.

By Scott DeJong

Defining a meme

The definition of a meme is somewhat contested. We worked with Milner and Philips (2017) who define memes as “evolving tapestries of self-referential texts collectively created, circulated, and transformed by participants online” (p.30). While recognizing that this definition includes video, sound and text memes, for the sake of collection and analysis we chose to gather text-based memes. Importantly, the definition understands memes as re-contextualized cultural artifacts, which highlights the importance of participants in the meme-making and circulation process. In this manner, memes are not simply combined images and text, rather they are invoked within a community process where the audience and creators are in conversation. For example, our project has focused on meme groups and pages on social media. These are specific online communities that conceive of the content they produce as memes. Often this is indicated in the name or handle by mention of memes or memetic “dankness” (Moody-Ramirez & Church, 2019).

Each meme page that we included in our analysis had a clear target audience in mind. By conceiving themselves as memetic, the creators of the pages indirectly make all content that is posted a form of satire. The context of the page can make information a “meme”. A prime example is the Facebook meme page Justin Trudno. The name immediately informs audience members that it is an anti-Prime Minister Trudeau page that posts content that enforces this sentiment. The page is clearly targeting non-Liberal voters and, through memes, engages audience members in discussion.

Considerations

We had been studying memes since the 2019 Canadian federal election and wanted to clarify our methods for the project, especially as we have since expanded our meme research to include content related to the COVID-19 pandemic. We started by considering the different roles in the space that we wanted to explore. Shifman (2014) argues that as researchers, we need to understand the different positions around a post alongside the meme, specifically considering “the ways in which addressers position themselves in relation to the text, its linguistic codes, the addressees, and other potential speakers.” (p. 40). Her argument stresses the importance of considering the multiplicity of positions that create the memetic conversation and of exploring a memetic community, not just individual posts. For us, this meant recording comments and general conversation on the page alongside the actual meme.

Milner and Philips (2017) offer a similar line of argument with their notion of ‘constitutive humour’. They posit that memes use humour to develop a specific in-group and to establish an ‘other’ that either does not understand the humour or is directly mocked by it. As researchers, this meant we had to consider who was ‘in’ the in-group and who was excluded, ourselves included. Recognizing that we are positioned as audience members in relation to these memes, our methodology made space for our own personal reflections and thoughts on the subject matter, which allowed us to explore our own bias and subjectivity in relation to the content.

Based on these considerations, we followed an ethnographic approach, spending time journaling and exploring the meme communities. Concepts like visual ethnography (Pink, 2007) initially seemed like a good fit, however considering that memes are repurposed and recontextualized across different partisan meme communities we turned to the idea of netnography. We drew on Kozinets’ (2010) work on netnography that considers how netnography can be used to explore community discussion, focusing on the content that is being shared and how it is taken up within the group. He specifically discusses the notion of consociality writing: “consociality is about ‘what we share’, a contextual fellowship, rather than ‘who we are’, an ascribed identity boundary such as race, religion, ethnicity or gender. The two forms are distinct and, even though one can shade or lead into the other, we should be careful not to systematically confound them.“ (Ibid. p. 11). Since memes exist as elements of community discussion, it is important to consider not just the memes being shared but the other content, conversations and discussion that is occurring on the page.

Our current methodology

In an effort to contribute to understanding the pandemic as communication and cultural studies scholars, we decided to implement these ideas into a meme collection methodology. With a smaller team we revisited our initial 21 political meme pages and did a historical review back to their first posts about the coronavirus in late February 2020.Then we chose five pages from Facebook and five from Instagram (see table below). Starting in May 2020, we dedicated an hour or more to each of these pages per week. During this time, we took screenshots of memes, comments, and content, and evaluated what issues were pertinent to the page over the course of that week. After the first two weeks of collection, we revisited our chosen meme groups. Realizing that some did not post very frequently, we added two more meme groups (included in the above numbers) and began tracking the lower frequency post groups bi-weekly.

Netnography proposes taking observational notes. Connecting this with work on diary as a method (Berg & Düvel, 2012) we decided to keep a journal about the research findings while also recording posts in a spreadsheet. We divided the journal into the following sections: the overall issue that the meme is addressing, the format that is being used in the meme, how the audience responds to it, our personal reflections, and a summary about the page and its content. Stirling (2016) emphasizes the importance of putting screenshots in your journals, which we incorporated to provide examples in our writing.

In addition, we also recorded posts in a spreadsheet and manually coded popular coronavirus memes on the pages using an inductive codebook. Coupled with this, we created a dashboard using Crowdtangle which allowed us to monitor and collect memes beyond the ones gathered and coded.

Conclusion

We have been using this method for the past month and plan on continuing to do so until at least the end of August. So far, this method has been an effective way to understand the conversation, dialogue and backstory to the memes being posted by the groups. We have come across memes where commenters argue about the posted meme’s message, and have also contextualized how news posts and other content plays into the memetic conversation on these pages.

By keeping these journals over time, we have watched the memespace change, caught similarities between typically disparate meme groups and tracked conversation change during the pandemic as other large events (like Black Lives Matter protests) occurred. While we are still refining our methodology, the mix of qualitative journaling with quantitative data collection helps construct an effective view of partisan meme space during COVID-19.

The funding for this project comes from the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship (CSDC).

References

- Berg, M., & Düvel, C. (2012). Qualitative media diaries: An instrument for doing research from a mobile media ethnographic perspective. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 3(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc.3.1.71_1

- Elmer, G., Langlois, G., & McKelvey, F. (2012). The Permanent Campaign: New Media, New Politics. Peter Lang.

- Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online. SAGE Publications.

- McKelvey, F., Côté, M., & Raynauld, V. (2018). Scandals and Screenshots: Social Media Elites in Canadian Politics. In A. Marland, T. Giasson, & A. Lawlor (Eds.), Political Elites in Canada: Power and Influence in Instantaneous Times (pp. 204–222). UBC Press.

- Milner, R. M., & Phillips, W. (2017). The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Polity.

- Moody-Ramirez, M., & Church, A. B. (2019). Analysis of Facebook Meme Groups Used During the 2016 US Presidential Election. Social Media + Society, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118808799

- Nielsen, R. K. (2020, May 22). Communications research has a lot to offer during the coronavirus crisis. But are we offering it? Rasmuskleisnielsen.net. https://rasmuskleisnielsen.net/2020/05/22/communications-research-has-a-lot-to-offer-during-the-coronavirus-crisis-but-are-we-offering-it/

- Pink, S. (2007). Doing Visual Ethnography. SAGE Publications, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857025029

- Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. The MIT Press.

- Stirling, E. (2016). ‘I’m Always on Facebook!’: Exploring Facebook as a Mainstream Research Tool and Ethnographic Site. In H. Snee, C. Hine, Y. Morey, S. Roberts, & H. Watson (Eds.), Digital Methods for Social Science: An Interdisciplinary Guide to Research Innovation (pp. 51–66). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137453662_4